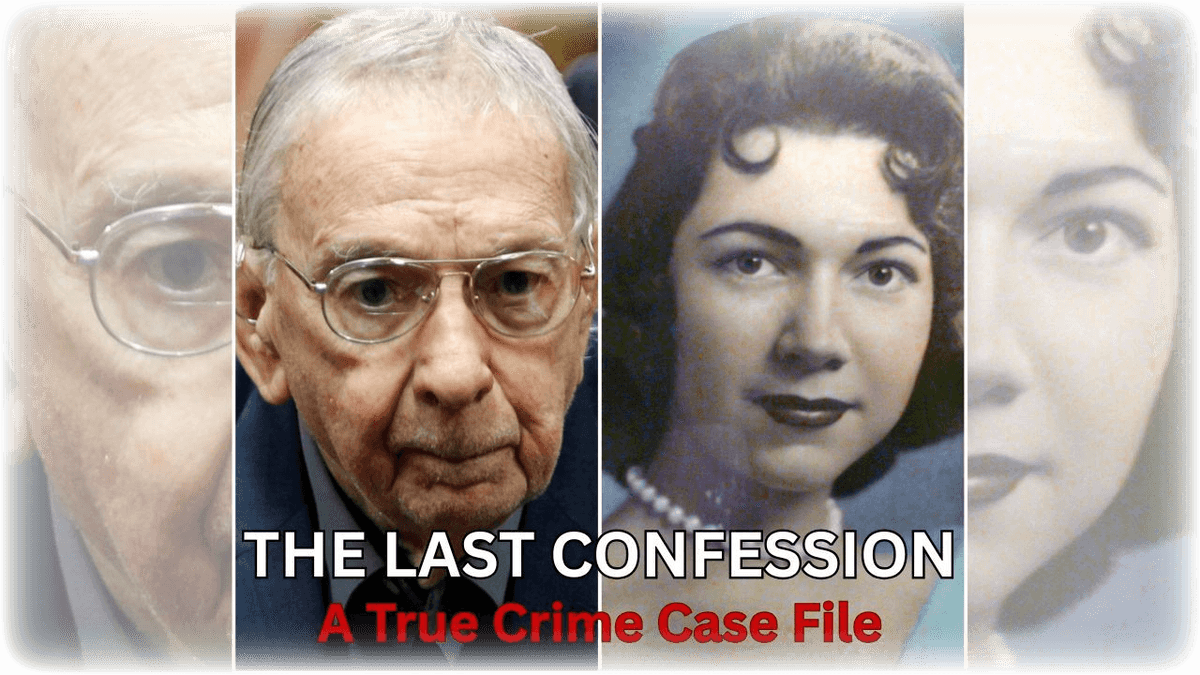

The Last Confession

Sacred Heart, Holy Saturday, and the Priest Who Got Away with Murder for 57 Years

The high heels click on the concrete walkway. Click. Click. Click. It is the sound that will haunt him, the priest will later confess—not the woman's face, not her pleas, not even what he did to her. Just the sound of her heels on the hard floor.

Holy Saturday, April 16, 1960. The sun drops behind the palm trees lining Beaumont Avenue in McAllen, Texas, and Irene Garza checks her reflection one more time. Twenty-five years old, dark hair perfectly set, lavender blouse pressed, black patent leather heels polished. She tells her parents she's going to confession at Sacred Heart Catholic Church—routine for a woman who attends daily Mass, who serves with the Legion of Mary, who teaches second grade to the poorest children on McAllen's south side.

She drives the seven blocks to Sacred Heart. Parks on the street. Walks toward the church in those black heels, carrying her patent leather purse. Several parishioners see her enter. No one sees her leave.

Inside the rectory next door, a 27-year-old visiting priest named John Bernard Feit is hearing confessions. Horn-rimmed glasses. Dark hair. Neat. Unremarkable. Temporary assignment from San Antonio, helping with Holy Week crowds. He's been in the Valley for exactly three weeks.

The next morning is Easter Sunday. Irene doesn't come home for breakfast. By noon, Nicolas Garza files a police report. His daughter never came back from confession.

The Border and the Power Structure

McAllen sits eight miles from the Mexican border, the northernmost edge of a cultural corridor that stretches back to Spanish colonial times. In 1960, the Rio Grande Valley is overwhelmingly Hispanic, overwhelmingly Catholic, and the church holds a power here that extends beyond Sunday services. Priests are authority figures. To question a priest is to question God himself.

The Garzas had worked their way into Anglo McAllen, moved north of the railroad tracks where success meant something. Irene was their pride—first Latina drum majorette at McAllen High, Miss All South Texas Sweetheart 1958, first in the family to graduate college. When something happens to Irene Garza, people notice.

The same cannot be said for what happens three weeks earlier, on March 23, 1960, in the town of Edinburg, ten miles from McAllen.

Twenty-year-old Maria America Guerra goes to church to pray. Inside the sanctuary, someone grabs her from behind, tries to force a rag over her mouth. She fights. She bites his finger hard enough to draw blood. She escapes. Later, she picks Father John Feit out of a lineup. He is arrested, charged with assault with intent to rape. His religious order, the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate, stands behind him.

Three weeks pass. Then Irene Garza goes to confession.

DID YOU KNOW? In 1960, face-to-face confession in a rectory was highly unusual in Catholic practice. The standard was confession through a screened booth where the priest could not see the penitent. Several witnesses testified that Father Feit had a pattern of pulling attractive young women out of the confessional to hear their confessions face-to-face in the rectory—a violation of both custom and Church guidelines designed specifically to prevent improper contact.

Five Days in April

Easter Sunday morning. Irene's car is still parked on the street near Sacred Heart Church. By evening, volunteer searchers fan out across McAllen. Monday, April 18, a beige high-heeled shoe is found near the church. Her patent leather purse turns up in a field.

Thursday, April 21. Five days after she disappeared. A body floats in an irrigation canal. Face down. Fully dressed except for shoes and underwear. Lavender blouse unbuttoned.

The autopsy tells the story: beaten with a hard object, sexually assaulted while unconscious, suffocated. Any physical evidence washed away by days in the water.

When police drain the canal, they find a green Kodak slide viewer with a long cord. On May 3, Father John Feit sends them a note: the viewer is his.

Detectives focus on Feit almost immediately. He admits hearing Irene's confession the night she disappeared, though his story changes. He has scratches on his hands. The polygraph examiner tests him—the initial report says he passed, then gets edited to say "inconclusive." Decades later, the examiner admits Feit failed.

But Irene's murder case stalls. No arrest. No charges. On August 6, 1960, a warrant is finally issued for Feit's arrest in the Guerra assault case. Police can't find him. He's vanished. A week later, he surrenders, claiming he checked into a hospital because his "nervous system was affected."

The Maria America Guerra assault trial ends in a hung jury. Rather than face a second trial, in February 1962, Feit pleads no contest to a reduced charge of aggravated assault. His punishment: a $500 fine. No jail time.

As for Irene Garza's murder? No charges are ever filed.

DID YOU KNOW? The year 1960 was a pivotal moment for Catholic political power in America. John F. Kennedy was running for president as the first Catholic candidate with a real chance of winning. In South Texas, where most elected officials were Catholic and the church wielded enormous influence, the idea of prosecuting a priest for murder during an election year where Catholics were fighting for national acceptance created a political minefield that local authorities chose not to navigate.

Where Systems Broke

Deputy Sheriff Milo Ponce sits at his kitchen table, crying. His young daughter Noemi has never seen her father cry before. He's been ordered to turn in all his investigative records on the Irene Garza case. His superiors tell him they'll handle it from here. They don't.

Years later, a television reporter testifies about a conversation with Hidalgo County District Attorney Robert Lattimore. Off the record, Lattimore told him, "We know that Father Feit killed Irene Garza and the church knows that he killed Irene Garza so we have made some arrangements." The church would send Feit to a monastery. He'd be kept there for the rest of his life. Justice would be served—just not the legal kind.

The arrangement didn't hold. Feit moved from monastery to monastery, then to a treatment center for troubled priests in New Mexico. He joined the staff in a supervisory role. When a priest named James Porter came to the center after molesting children, Feit cleared him for placement in another parish. Porter later abused as many as 100 children.

At Assumption Abbey in Ava, Missouri, where Feit is sent in 1963, an abbot asks a young Trappist monk named Dale Tacheny to counsel the new arrival. Tacheny asks Feit why he's at the monastery instead of in prison. Feit lists three things that helped him avoid charges: the Catholic Church, law enforcement, and the seal of confession.

Then he tells Tacheny about a young woman in Texas. Around Easter. After confession. He assaulted her, bound her, took her to the basement of the rectory, transported her to the pastoral house, put her in a bathtub. He heard her say, "I can't breathe. I can't breathe." When he returned, she was dead.

Tacheny asks if Feit feels remorse. Feit says no. He just gets anxious when he hears high heels clicking on a hard floor.

Tacheny doesn't go to police. The monastery eventually concludes Feit isn't fit for monastic life. Feit leaves the priesthood in the early 1970s, marries, has three children, settles in Scottsdale, Arizona. He volunteers at St. Vincent de Paul for seventeen years.

Tacheny carries his secret for 39 years.

The Long Road to Justice

In 2002, Dale Tacheny, now 73, is approached about writing his life story. The memory of John Feit's confession resurfaces. He calls San Antonio police. A Texas Ranger makes the connection: McAllen. Irene Garza. 1960.

Around the same time, McAllen Police Chief Victor Rodriguez reopens the case. Texas Rangers join the investigation. Ranger Rudy Jaramillo hangs Irene's photograph in his office. Father Joseph O'Brien, who worked with Feit in 1960, admits what he's hidden for 42 years: Feit confessed shortly after Irene's death.

Two witnesses. Two confessions. A case reopened.

But Hidalgo County District Attorney Rene Guerra isn't interested. "Why would anyone be haunted by her death?" he asks in 2002. "She died. Her killer got away." When reporters ask if the case will ever be solved, Guerra says, "If you believe pigs can fly."

Irene's cousin Lynda de la Viña becomes the public face of their fight. In 2004, Guerra brings the case before a grand jury, but doesn't subpoena Feit, Tacheny, or O'Brien to testify in person. They vote not to indict. Father O'Brien dies in September 2005.

The family doesn't stop. They make "Justice for Irene" a rallying cry. In 2014, district court judge Ricardo Rodriguez challenges Guerra in the DA election, promising to review the case with fresh eyes. Rodriguez wins.

On February 23, 2016—56 years after Irene's murder—police arrest John Bernard Feit at his home in Scottsdale, Arizona. He is 83 years old.

The trial begins November 30, 2017. Dale Tacheny, now 88, gives emotional testimony. He breaks down when asked why he finally came forward. "She had parents," he whispers.

On December 7, 2017, after six hours of deliberation, the jury finds John Bernard Feit guilty of murder with malice. The next day, he is sentenced to life in prison.

Lynda de la Viña speaks to reporters outside the courthouse. "Pigs are flying tonight."

Feit dies on February 13, 2020, at age 87, having served less than three years of his sentence.

DID YOU KNOW? The Irene Garza case prompted changes to Texas law regarding the statute of limitations for sexual assault and the handling of cold cases. It also contributed to national conversations about institutional cover-ups of clergy abuse, joining cases like those documented in the Boston Globe's Spotlight investigation. McAllen's diocese conducted a review of its historical handling of abuse allegations and implemented new mandatory reporting protocols.

Why This Still Matters

The Irene Garza case isn't just a story about a priest who got away with murder for 57 years. It's a map of how power protects itself, how institutions value reputation over truth, how justice gets delayed until everyone who could have stopped it is dead or too old to care.

When Irene walked into Sacred Heart Church on Holy Saturday 1960, she carried with her all the trust that faith demands. Father Feit violated the boundary the Church itself established to prevent exactly what he did.

The cover-up that followed reveals the mechanics of institutional self-preservation. Better to ship Feit to a monastery than prosecute him and embarrass the church during JFK's presidential campaign. Better to protect the institution than seek justice for one woman, even a woman as beloved as Irene Garza.

What breaks the cycle? Persistence. Dale Tacheny carrying guilt for 39 years until he couldn't anymore. Lynda de la Viña and Noemi Ponce Sigler refusing to let the case die. Ricardo Rodriguez making justice for Irene a campaign promise and keeping it.

The trial became a referendum on institutional power. The jury convicted Feit not just on the evidence but on the accumulated weight of decades of lies, evasions, and cover-ups. They sent a message: institutions don't get to protect their own at the expense of truth.

But the victory is incomplete. Irene is still dead. Her parents died not knowing justice would ever come. John Feit spent most of his life free—married, raised children, volunteered at charities, lived in Arizona sunshine while Irene remained frozen at 25 in the photographs her family kept on their walls.

The case exposes a troubling reality: the mechanisms exist to protect abusers. Transfer them. Send them to monasteries. Get them treatment and return them to ministry. Feit himself cleared James Porter for parish work. Porter went on to abuse 100 children.

Today, mandatory reporting laws in Texas require anyone with knowledge of abuse to report it immediately. But laws only work when people enforce them. The real lesson is that justice requires individuals willing to risk comfort, career, and social standing to pursue truth.

When Lynda de la Viña said "pigs are flying tonight" after the verdict, she was reclaiming power. The former DA who told her justice was impossible was proven wrong. The institutional forces that protected Feit for decades were defeated.

Irene Garza was 25 years old when she died. She taught second-graders on McAllen's poor south side, bought them shoes and school supplies when they needed them, went to Mass daily. She wrote letters about finding happiness, about conquering her fear of death through faith.

Her faith is what killed her.

The man who heard her last confession used that sacred trust to pull her into a room alone. He assaulted her. He bound and gagged her. He put her in a bathtub and listened to her say "I can't breathe" as he walked away. He dumped her body in a canal like garbage.

And for 57 years, he walked free because the institutions that should have protected her chose to protect him instead.

That's why this case still matters. Because institutions still choose self-preservation over justice. Because abuse still gets hidden. Because victims still get told their pain matters less than reputation. Because it takes extraordinary effort to make the powerful answer for their crimes.

But it can be done. Pigs can fly. And sometimes, if enough people refuse to accept the unacceptable, justice arrives late but arrives nonetheless.

Case Timeline

March 23, 1960 – Maria America Guerra attacked at church in Edinburg, Texas; identifies Father John Feit as attacker

April 16, 1960 – Irene Garza goes to confession at Sacred Heart Catholic Church, McAllen; never returns home

April 17, 1960 – Nicolas Garza files missing person report on Easter Sunday

April 21, 1960 – Irene's body discovered in irrigation canal; autopsy reveals sexual assault, beating, suffocation

May 3, 1960 – Father Feit sends note to police identifying slide viewer as his

August 6, 1960 – Arrest warrant issued for Feit in Maria America Guerra assault case

August 13, 1960 – Feit surrenders after one week missing

September 1961 – Feit's trial for assault ends in hung jury

February 1962 – Feit pleads no contest to reduced charge; fined $500; serves no jail time

1963 – Feit sent to Assumption Abbey; confesses murder to monk Dale Tacheny

Early 1970s – Feit leaves priesthood; marries; moves to Scottsdale, Arizona

April 2002 – Dale Tacheny contacts San Antonio police with information about Feit's confession

2002 – Texas Rangers reopen investigation

2004 – Grand jury declines to indict

2014 – Ricardo Rodriguez defeats Rene Guerra in DA election

February 23, 2016 – John Feit arrested in Scottsdale, Arizona, at age 83

December 7, 2017 – Jury convicts Feit of murder with malice

December 8, 2017 – Feit sentenced to life in prison

February 13, 2020 – John Feit dies in prison at age 87

Sources

1. Texas Department of Public Safety – Cold Case Investigation Files, Case #151 (Irene Garza)

2. "Murder of Irene Garza," Wikipedia (verified against primary sources)

3. "Unholy Act," Texas Monthly, Pamela Colloff (2005)

4. "The Last Confession," CBS News 48 Hours investigation (2014-2018)

5. Courthouse News Service coverage of trial and appeals (2017-2019)

6. Associated Press trial coverage (November-December 2017)

7. San Antonio Express-News trial coverage (November-December 2017)

8. The Monitor (McAllen, TX) archival coverage (1960-2017)

9. Trial transcripts and court documents, 92nd District Court, Hidalgo County, Texas

10. "Darkness: The Murder of Irene Garza" podcast series, The Drag Audio (2025)

MACABRE TRUE CRIMES & MYSTERIES: 20 SOLVED AND UNSOLVED TALES FROM AROUND THE WORLD - Volume #4 by Guy Hadleigh

Blog written by Guy Hadleigh, author of Crimes That Time Forgot, the Macabre True Crimes & Mysteries Series, the Murder and Mayhem Series, the British Killers Series, the Infamous True Crimes and Trials Series - and many more!

Have questions?