Six Icelanders admit to two murders they can’t remember, sparking a decades-long

battle over police tactics, false memories, and one of Europe’s strangest miscarriages of justice.

The Disappearances - A Dark Night in January 1974

In the early hours of 26 January 1974, 18-year-old Guðmundur Einarsson left a community dance hall in Hafnarfjörður – a small port town just outside Reykjavík – and set out on foot for home. A winter storm was raging, blanketing the lava fields of the Reykjanes peninsula in thick snow. Guðmundur had been drinking and, with youthful overconfidence, decided to walk the 10 km journey despite the perilous weather. On a remote dark road, a driver later reported nearly hitting a stumbling figure who lurched in front of his car – believed to be the young man himself. That motorist drove on, leaving Guðmundur alone in the blizzard, and the teenager was never seen again.

Search parties mobilized in the following days once Guðmundur was reported missing. They scoured the snowbound lava fields and rocky crevasses where a person could easily disappear. The hunt was hampered by drifts half a meter deep, and after a few weeks the authorities called it off with no trace found. In Iceland, it was not unheard-of for people to vanish in harsh winter storms without a trace – a tragic reality often attributed to the unforgiving landscape and weather. Many assumed Guðmundur’s fate was just such a misfortune of nature (speculation). His name might have faded from public memory as an unfortunate statistic – if not for what happened next.

Ten Months Later: Another Man Missing

Boats docked in Keflavík harbor, where search teams scoured the waters for any sign of the missing man. Geirfinnur Einarsson, a 32-year-old construction worker and family man from the town of Keflavík, vanished on 19 November 1974 under eerily similar circumstances. That evening, Geirfinnur was relaxing at home when he received a mysterious phone call. He promptly drove to a café by the harbor and parked outside, leaving the keys in the ignition of his car – but he never returned to the vehicle. In the frosty darkness of a November night, this devoted father of two disappeared without a trace.

The police treated Geirfinnur’s case with urgency. Investigators converged on Keflavík harbor, scouring the docks, icy waters, and surrounding lava rocks for any clue. An extensive search of the harbor and rugged coastline turned up nothing – no body, no evidence. Determined to leave no stone unturned, the lead detective sifted through Geirfinnur’s personal life for answers. They examined his bank records, mail, and relationships for any hint of motive or foul play, yet came up empty-handed. Ten months after Guðmundur’s unexplained vanishing, Iceland was now faced with a second man gone missing in the span of a year. Two men – both ordinary, unrelated individuals – had seemingly vanished into thin air on the southwest coast of Iceland, and nobody could explain how or why.

A Perplexed and Frightened Nation

The twin disappearances sent a chill through Iceland’s tightly knit society. In 1974 the entire country’s population was only about 220,000 – small enough that people felt they practically knew each other. Violent crime was exceedingly scarce; years could pass without a single murder, and the notion of strangers falling victim to foul play was almost unthinkable. When news spread that two men had vanished without a trace, the public was bewildered and alarmed. Many Icelanders, unaccustomed to such mysteries, were gripped by a creeping unease (speculation). No bodies, no witnesses, no forensic evidence – nothing – it was as if Guðmundur and Geirfinnur had simply evaporated into the dark Icelandic winter.

The media latched onto the story, amplifying the sense of dread. Headlines asked uncomfortable questions: Was there a killer lurking in this peaceful nation, or were these accidents of fate? Under intense public and press pressure, the authorities felt they had to solve the puzzle of the missing men. The police, still haunted by an unsolved 1968 murder in Reykjavík (see sidebar below), were determined not to fail again. Yet by the summer of 1975, despite exhaustive efforts, both cases remained bafflingly cold – no leads, no answers. Icelanders were left to wonder if they would ever learn the truth.

Did You Know?

In 1968, a taxi driver was fatally shot in Reykjavík – a rare crime in peaceful Iceland. The case was never solved, haunting the public throughout the decade and pressuring police. That unsolved mystery loomed large for the insular community when two men vanished in 1974.

Rumors and Theories Emerge

With official investigations at a standstill, theories and rumors began to swirl in smoke-filled cafés and taverns. Some locals speculated that Guðmundur had simply succumbed to the elements after a night of heavy drinking – a tragic accident rather than foul play (speculation). Others wondered if Geirfinnur might have accidentally fallen into the sea at the Keflavík docks, his body lost to the frigid Atlantic (speculation). More sinister whispers suggested that something criminal was afoot: one persistent rumor claimed Geirfinnur had been involved in illegal alcohol smuggling and met with trouble that night. The police found no evidence to support the smuggling theory, but such talk kept the public on edge. In the absence of hard facts, each new rumor – however outlandish – gained a foothold in the public imagination.

Facing mounting criticism and desperate for a breakthrough, the Icelandic police took the unusual step of officially opening a murder inquiry despite having no bodies or physical clues to go on. This was virtually unprecedented – two presumed murders with zero forensic evidence. The pressure on investigators to get results was enormous. They began listening intently to the murmurs on the streets of Reykjavík and Keflavík, chasing even the faintest hints. Before long, one name from the underbelly of Reykjavík’s petty criminal scene kept surfacing in those hushed conversations. Police heard whispers that a young small-time crook “knew something” about the disappearances. In late 1975 – nearly two years after the first man went missing – detectives finally latched onto this lead. The strange saga was about to take an even darker turn, as attention fell on an unlikely suspect: a twenty-year-old man named Sævar Ciesielski. The stage was set for a baffling investigation that would soon veer into the surreal – and ultimately make history as “the Reykjavík Confessions.”

Investigation

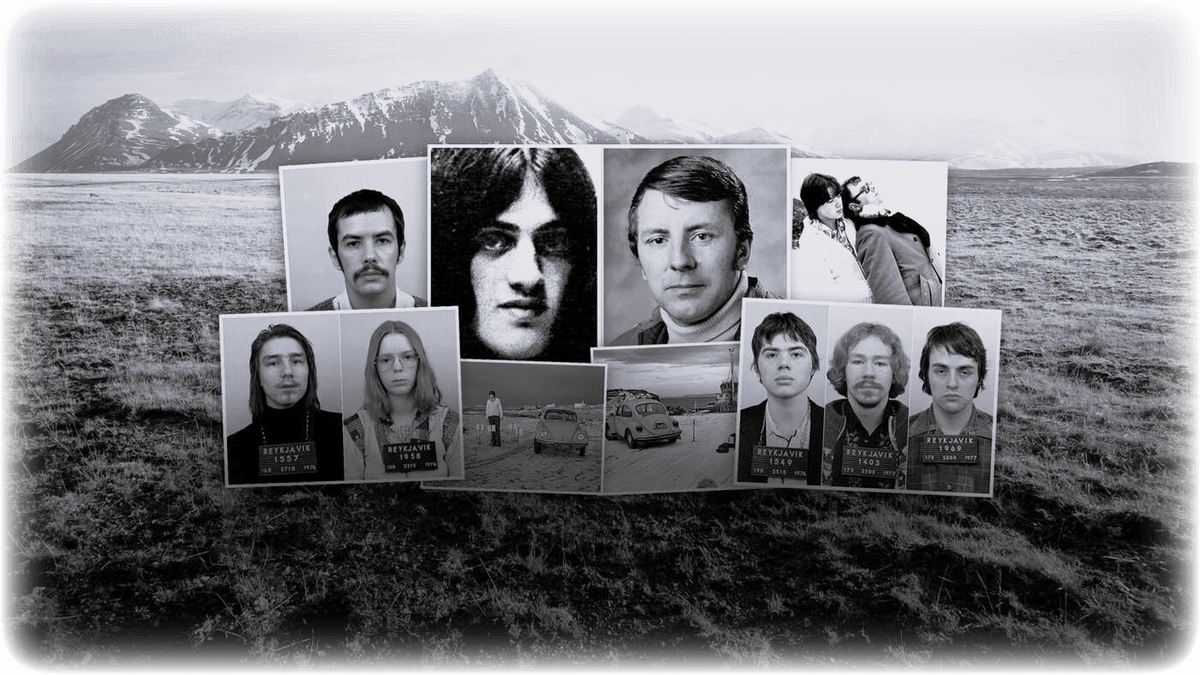

By late 1975, public faith in the police was waning. Two men had vanished in a peaceful country unused to violent crime, and investigators had nothing—no bodies, no murder weapons, no suspects. But pressure from the media, politicians, and the public mounted by the day. A small-time Reykjavík criminal named Sævar Ciesielski, then just 20 years old, was arrested for theft in December 1975. While in custody, police questioned him about the disappearances of Guðmundur and Geirfinnur. That line of questioning would mark the beginning of one of the most bizarre—and controversial—investigations in Icelandic history.

Sævar’s background made him an easy target. A troubled youth with a minor criminal record, he was known in the city’s underground scene. He also had a Polish surname—unusual in Iceland—which made him stand out. But what made him most vulnerable was this: he had no strong alibi, and he was deeply suggestible under pressure. What followed would spiral far beyond any simple interrogation.

Icelandic police brought in Sævar’s girlfriend, Erla Bolladóttir, who had been involved in the same petty crimes. Erla initially denied knowing anything about the disappearances. But after hours of questioning and intimidation, she recalled a dream in which she saw a dead body being disposed of. That dream would be interpreted as a memory, not a fantasy. Investigators took it as evidence that she had witnessed a murder.

Investigator Profile

At the time of the investigation, Iceland’s police were under immense pressure due to an unsolved murder in 1968 and rising political scrutiny. Though no one officer was solely responsible, the methods used—including extended isolation, leading questions, and psychological pressure—were later condemned by international human rights experts.

Bizarre Trivia

Iceland had no experience with extended solitary confinement before this case. After Reykjavík Confessions unraveled decades later, international experts noted that only countries under authoritarian regimes had used such long isolation tactics at the time.

This moment set the tone for everything that followed.

Erla was held in solitary confinement for 105 days—interrogated repeatedly without access to a lawyer, denied contact with her family, and subjected to sleep deprivation. Eventually, she began to give the police what they wanted: names. She named Sævar, and then four others: Kristján Viðar Viðarsson, Tryggvi Rúnar Leifsson, Guðjón Skarphéðinsson, and Albert Klahn Skaftason . All were arrested.

Police claimed they had cracked the case. Six suspects. Two murder victims. But they still had no bodies, no forensic evidence, and no eyewitnesses outside the accused themselves.

To fill in the blanks, they leaned hard on psychological interrogation tactics. All six suspects were held in solitary confinement for extended periods—Sævar for over 600 days, Tryggvi for 655 days, and Guðjón for nearly 700 days. These were extreme conditions even by international standards at the time.

The interrogations became infamous. Sleep deprivation, hallucinogenic medication, and intense suggestive questioning were used over and over. At times, police fed the suspects false information, including “evidence” that didn’t exist. Eventually, under this pressure, each suspect began to confess—not just to the police, but to themselves.

They began to question their own memories. Several claimed they had memory gaps, or that they could no longer tell the difference between dreams and reality. Guðjón reportedly asked officers, “Is it possible I did this and forgot?” The answer he received: “Yes.”

What makes the Reykjavík Confessions so disturbing is that the suspects weren’t confessing to protect someone else, or under physical torture—they were confessing because they had begun to believe they were guilty, despite the absence of evidence. What unfolded was a chilling example of memory distrust syndrome, where prolonged isolation and mental manipulation created false memories.

Outside the interrogation rooms, the Icelandic public was largely unaware of what was happening. The police presented the arrests as a major success. They had solved not one but two murders with no bodies. Newspapers ran celebratory headlines. A nation that had feared a murderer was now able to sleep again.

But inside the cells, a psychological storm was unfolding.

Bizarre Trivia

Iceland had no experience with extended solitary confinement before this case. After Reykjavík Confessions unraveled decades later, international experts noted that only countries under authoritarian regimes had used such long isolation tactics at the time.

When the doors of the prison cells finally closed behind the Reykjavík Confessions suspects, most Icelanders tried to move on. The public had been told that justice was served. But the six people who had confessed to crimes they could not recall—and for which no bodies, weapons, or physical evidence had ever been found—were now left to live with the aftermath of a justice system that had broken them to get a confession.

For Sævar Ciesielski, the psychological damage was profound. Once a charismatic, energetic young man, prison turned him into a shell. After his release in the 1980s, he never regained stability. He lived in poverty, often homeless, and struggled with addiction and mental health issues. He spent the rest of his life proclaiming his innocence to anyone who would listen. “They made me say it,” he said. “They put the memory into my head.” Sævar died in Copenhagen in 2011, just as momentum for a legal re-examination of the case began to mount.

The others fared little better. Erla Bolladóttir, only 20 when she was imprisoned, moved abroad and wrote a memoir years later detailing the trauma of her incarceration and how she’d come to doubt her own mind. Tryggvi Rúnar Leifsson reportedly lived in complete social isolation after his release, deeply scarred by his 655 days in solitary confinement—one of the longest on record in a democratic nation.

Where Are They Now?

Only Erla Bolladóttir remains alive and publicly active, now living abroad. The others either died or faded into obscurity. Their convictions were formally overturned in 2018, too late for most to see justice done in their lifetimes.

Yet even as their lives quietly unraveled, the wheels of justice turned slowly. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that the cracks in the case began to receive serious attention again. A growing body of international psychological research into false confessions and memory distrust syndrome brought new scrutiny to the case. British journalist Simon Cox produced a BBC documentary that brought the story to a wider audience, describing it as “one of the most chilling examples of institutional failure in modern legal history.”

In 2011, the Reykjavík Confessions were officially reopened for re-examination by Iceland’s government. An independent working group was appointed, tasked with reviewing the investigation and convictions using modern legal standards. What they uncovered was damning: procedural failures, coerced confessions, abuse of solitary confinement, and a total absence of corroborating evidence. Even the case judge, it turned out, had privately expressed doubt at the time of conviction.

In 2018—44 years after Guðmundur and Geirfinnur vanished—Iceland’s Supreme Court formally acquitted five of the six defendants. Only Erla’s perjury conviction remained, though even that was viewed as part of the broader miscarriage of justice. The court acknowledged that the convictions had been “based on confessions made under duress, in conditions incompatible with a fair trial.”

But no one had been held accountable. No charges were brought against the detectives involved. No disciplinary actions were taken. The police force, under pressure in the 1970s to solve a national mystery, had delivered a solution—but one that came at the cost of truth.

As for the original mystery, it remains just that. Guðmundur Einarsson and Geirfinnur Einarsson are still missing. No bodies have ever been recovered. No forensic breakthroughs have been made. Some still believe that Guðmundur simply perished in the snow after a night of drinking, his body lost in the rugged terrain. Geirfinnur’s disappearance remains more sinister. A few former investigators continue to suspect he may have been killed in a dispute over illegal alcohol—but again, no hard evidence has ever emerged.

In recent years, the Reykjavík Confessions have been taught in law schools around the world. They are cited in academic papers and conferences on interrogation ethics, memory malleability, and justice under pressure. Iceland, a nation that once prided itself on near-zero crime, was forced to reckon with a truth darker than any murder: its legal system, when pressed, had sacrificed reality for resolution.

Similar Bizarre Cases

Comparable cases include the Central Park Five in the U.S. and the Norfolk Four, where false confessions under duress led to wrongful convictions. Like the Reykjavík Confessions, these cases hinged on interrogations that overwhelmed the suspects’ sense of reality.

Timeline of Events:

Jan 26, 1974

– Guðmundur Einarsson disappears after walking home from a party.

Nov 19, 1974

– Geirfinnur Einarsson vanishes after a phone call and trip to a harbor café.

Dec 1975

– Police arrest Sævar Ciesielski. Erla and four others follow.

1976–1977

– All six suspects held in solitary and interrogated; multiple confessions secured.

1977

– Five convicted of murder; Erla convicted of perjury.

1990s–2000s

– Renewed legal challenges begin.

2011

– Case reopened by Icelandic authorities.

2018

– Supreme Court formally acquits five; convictions ruled unjust.

Image Credit:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/the_reykjavik_confessions

Sources:

Primary source: Icelandic Supreme Court records and official case reviews (2011–2018)

News article: BBC News, “The Reykjavík Confessions: Iceland’s Greatest Miscarriage of Justice,” 2014

Secondary/Contextual source: Wikipedia entry: “The Guðmundur and Geirfinnur case,” incorporating reports from Icelandic justice system reviews and international legal analysis (retrieved 2024)

Blog written by Guy Hadleigh, author of Crimes That Time Forgot, the Macabre True Crimes & Mysteries Series, the Murder and Mayhem Series, the British Killers Series, the Infamous True Crimes and Trials Series - and many more!