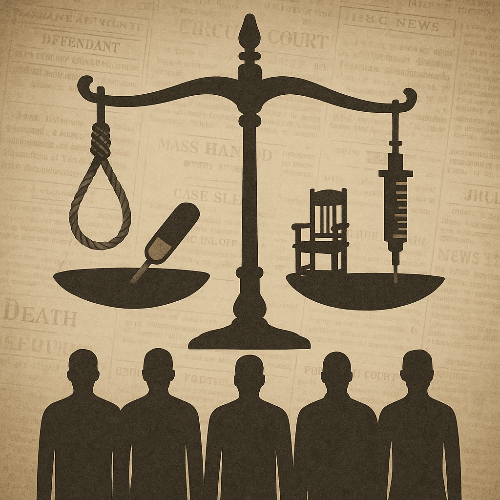

5 Cases Where the Wrong Person Was Executed

They were convicted, sentenced, and executed — but later evidence proved they were innocent. These tragic cases reveal how flawed trials and bad forensics cost innocent lives. Read the full story and uncover the darkest mistakes of justice.

The death penalty has long been justified as the ultimate punishment for the most serious crimes. But history shows us a darker truth: innocent men and women have gone to the gallows, the chair, and the needle. These are five cases where the wrong person was executed — tragic stories that expose the fallibility of justice.

1. George Stinney Jr. (South Carolina, 1944)

The case in brief:

On March 23, 1944, in the segregated mill town of Alcolu, South Carolina, two white girls—Betty June Binnicker (11) and Mary Emma Thames (7)—were found murdered in a waterlogged ditch after going missing while picking flowers. Within hours, deputies focused on George Stinney Jr., a slight, 90-pound Black seventh-grader who lived nearby with his family. He and his older brother had briefly spoken with the girls earlier that day.

The interrogation:

Deputies took George away without his parents (who said they were not allowed to see him) and without an attorney. Authorities later claimed he confessed, but no written or signed confession survives; what prosecutors presented at trial was a second-hand account of what officers said the boy told them. There was no physical evidence tying him to the murders—no blood, fibers, or weapon recovered from him or his home.

The trial in detail:

• Date & duration: April 24, 1944; the entire trial lasted about two hours.

• Defense: A single court-appointed attorney met George only briefly. The defense called no witnesses (not even George’s family to establish an alibi) and offered no expert testimony challenging the state’s theory.

• Jury: All-white, all-male jury in the Jim Crow South.

• Prosecution’s case: Primarily an alleged oral confession relayed by law enforcement and doctors’ testimony about the girls’ injuries.

• Deliberation & verdict: The jury deliberated around 10 minutes before returning a verdict of guilty of murder. No recommendation of mercy was made, which mandated the death penalty.

The execution:

On June 16, 1944, George—14 years old—was executed in the electric chair at the state penitentiary in Columbia. Contemporary accounts describe a horrifying scene: the chair and headgear built for adults did not fit his small frame; the mask slipped from his face after the first jolt, exposing the boy’s features to witnesses. He maintained to some that he was innocent.

Cultural Context

This was the deep Jim Crow South: rigid segregation, disenfranchisement, and racial terror shaped policing, prosecutions, and juries. In Alcolu, a company town divided by race and railroad tracks, the rapid arrest, cursory trial, and absence of meaningful defense reflected a system that routinely denied Black defendants due process.

The 2014 ruling (vacatur):

In December 2014, Circuit Court Judge Carmen Mullen vacated Stinney’s conviction, finding fundamental constitutional violations: a coerced confession from a child questioned without counsel or family; an inadequate defense; and a trial process so truncated it amounted to a “structural due process” failure. The court did not retry the facts of who killed the girls; instead, it held that the 1944 proceeding could not be considered a fair trial by any standard.

Aftermath and legacy:

• The ruling formally cleared George Stinney Jr.’s name, offering his surviving family a measure of vindication after seven decades.

• The case is now taught as a stark example of how race, poverty, and youth can combine to produce catastrophic miscarriages of justice.

• It continues to inform debates about juvenile interrogations, access to counsel, and the death penalty, especially for minors (now unconstitutional in the U.S.).

Legal Legacy

While the Supreme Court would not ban the execution of minors until Roper v. Simmons (2005), Stinney’s story has become emblematic of why such protections are necessary. It underscores modern safeguards: mandatory presence of guardians or counsel during juvenile questioning in many jurisdictions, heightened reliability standards for confessions, and greater scrutiny of all-white juries in racially charged cases.

Every pillar of a fair trial was compromised—coerced confession, no defense investigation, biased jury, no physical evidence—and the ultimate punishment was carried out against a child. The 2014 vacatur didn’t merely correct a paperwork error; it acknowledged that what happened in 1944 was not justice at all.

________________________________________

2. Timothy Evans (London, 1950)

Timothy John Evans was a young, semi-literate Welshman who moved to 10 Rillington Place, Notting Hill, London with his wife Beryl and infant daughter Geraldine in 1948. The upstairs flat was occupied by John Christie, a seemingly mild-mannered war veteran and special constable. Evans’s marriage was troubled: he drank heavily, the couple argued often, and money was scarce. In late 1949, the family’s difficulties turned into a nightmare that would end with Evans’s execution.

The disappearance of Beryl and Geraldine:

In November 1949, Beryl and baby Geraldine vanished. Evans, confused and frightened, told conflicting stories. At first, he claimed Beryl had died during a botched abortion attempt performed by Christie and that Christie promised to dispose of her body. Later, he suggested he himself had been partly responsible. The inconsistencies — possibly due to Evans’s limited intellect and Christie’s manipulations — would prove fatal.

Christie’s testimony:

Christie, the respectable neighbor, testified that Evans had confessed to strangling his wife during a quarrel. Christie painted himself as a reluctant witness to a volatile man’s crime. At the time, police had no reason to doubt him. When police searched the garden at 10 Rillington Place, they found the bodies of Beryl and Geraldine buried in an outhouse washhouse. With that, Evans was charged with two murders, though prosecutors proceeded only with Geraldine’s case, knowing jurors would react most strongly to the death of a child.

The trial:

• Date: January 1950 at the Old Bailey.

• Defense: Evans was represented by court-appointed counsel but mounted little effective challenge to Christie’s credibility.

• Prosecution’s case: Centered on Evans’s inconsistent statements and Christie’s testimony. Forensic evidence was scant; police work was cursory.

• Outcome: Evans was convicted of murdering his daughter and sentenced to death.

On March 9, 1950, he was hanged at Pentonville Prison, aged just 25. He maintained to the end that Christie was the true killer.

Cultural Context

Postwar Britain was still steeped in rigid class divisions and deferential attitudes toward authority. Christie, older, articulate, and seemingly respectable, was given credibility. Evans, a working-class Welshman with limited education, was easy to dismiss as unreliable.

Christie unmasked:

Three years later, in 1953, police investigating new murders at Rillington Place discovered multiple female corpses hidden in the walls, floorboards, and garden. The killer was John Christie himself, who confessed to strangling at least eight women between 1943 and 1953, including his own wife, Ethel.

Among his victims was Beryl Evans — proving that Evans’s initial claim that Christie was involved had been true. Christie’s confession exonerated Evans posthumously, though the process of overturning his conviction took decades.

Official recognition of miscarriage of justice:

• In 1966, after sustained campaigning, Evans was granted a posthumous pardon for the murder of his daughter Geraldine.

• In 2004, the British government issued a formal apology to Evans’s surviving family.

Legal Legacy

The Evans case became a watershed moment in the UK’s debate over the death penalty. The revelation that Britain had hanged an innocent man shook public confidence in capital punishment. Along with other controversial cases, it directly contributed to the abolition of the death penalty for murder in 1965.

Why this belongs in “Wrong Person Executed”:

Evans was condemned largely on the word of a serial killer who was later exposed as one of Britain’s most notorious murderers. His case illustrates how unreliable testimony, poor police work, and class prejudice can converge into a catastrophic miscarriage of justice — one that cost an innocent man his life and permanently scarred British legal history.

________________________________________

3. Cameron Todd Willingham (Texas, 2004)

On December 23, 1991, a fire broke out at the Corsicana, Texas, home of Cameron Todd Willingham, a 23-year-old mechanic. The blaze spread rapidly, and despite frantic efforts, his three daughters — Amber (2) and twins Karmon and Kameron (1) — perished in the flames. Willingham escaped with minor burns. From the start, local authorities suspected the fire was not accidental but deliberately set.

The investigation and “arson science”:

Fire investigators concluded that the blaze was the result of arson, pointing to:

• “puddle configurations” on the floor, allegedly showing accelerant use.

• Crazed glass (spider-web patterns in window glass), claimed to indicate rapid heating from accelerants.

• Low burn marks, said to prove fuel had been poured.

At the time, such indicators were widely accepted in fire investigation, though today they are considered myths. No chemical traces of accelerants were found in the debris.

The trial:

In 1992, Willingham was charged with capital murder. Prosecutors presented the fire marshal’s testimony as proof of deliberate arson. They also brought in jailhouse informant Johnny Webb, who claimed Willingham had confessed to him — a testimony later recanted, with Webb admitting he was pressured to lie.

The prosecution painted Willingham as a violent, unfeeling man with a troubled marriage, using his music tastes (heavy metal and Iron Maiden posters) and tattoos as evidence of a “satanic” nature. His alleged lack of grief in the aftermath was emphasized heavily.

The jury convicted him, and he was sentenced to death.

Cultural Context

In 1990s Texas, capital punishment was both common and politically charged. Prosecutors often relied on character assassination and outdated forensic methods, confident juries would side with the state. Willingham — a poor, working-class man with a rebellious streak — made an easy target for moral judgment as much as legal scrutiny.

Appeals and execution:

Willingham’s appeals failed despite his insistence on innocence. On February 17, 2004, he was executed by lethal injection in Huntsville, Texas. His last words declared love for his children and denied harming them.

Post-execution revelations:

Even before his execution, doubts about the case were surfacing. Fire scientist Dr. Gerald Hurst, a respected chemist and explosives expert, reviewed the evidence and concluded there was no credible indication of arson — the fire patterns cited by investigators could all be explained by ordinary flashover (when a room’s contents ignite almost simultaneously due to extreme heat).

After Willingham’s death, further independent reviews by the Innocence Project and the Texas Forensic Science Commission echoed Hurst’s findings: the original investigation had relied on junk science, and the fire was likely accidental.

Legal Legacy

The Willingham case became one of the most cited examples in the modern debate over the death penalty and wrongful execution. It underscored how “expert” testimony, unchecked by rigorous science, can condemn the innocent.

In 2009, the Texas Forensic Science Commission formally criticized the original arson investigation methods. However, the state has never officially exonerated Willingham.

Why this belongs in “Wrong Person Executed”:

Every independent modern review has concluded that the fire was not arson. Without the flawed forensics and dubious jailhouse testimony, there was no case against Willingham. Yet he was executed, leaving a legacy that continues to haunt Texas’s justice system. His story stands as a chilling reminder that wrongful execution is not only a historical problem but a very modern one.

________________________________________

4. Mahmood Hussein Mattan (Wales, 1952)

Mahmood Hussein Mattan was a Somali-born former merchant seaman who had settled in Tiger Bay, Cardiff — one of Britain’s oldest multicultural dockside communities. By the early 1950s, he was working odd jobs, separated from his Welsh wife, and raising three young sons. On March 6, 1952, shopkeeper Lily Volpert was murdered in her clothing store in Cardiff’s docklands. She was found with her throat slit, and her cash box missing.

The investigation:

Police quickly focused on Mattan, who was already known to them for minor offenses and who, as a Somali Muslim in a predominantly white city, stood out. Witnesses placed him “near” the shop, though accounts were contradictory and inconsistent. Police ignored or failed to pursue other potential suspects, including men with histories of violence and robbery.

The trial flaws:

• Racist atmosphere: During the trial, Mattan’s defense counsel referred to him in open court as a “semi-civilised savage.” Such language poisoned the jury’s perception.

• Unreliable witnesses: The prosecution relied heavily on the testimony of witnesses with poor credibility, including one who later admitted he had lied.

• Withheld evidence: Police and prosecutors withheld key exculpatory evidence, including witness statements that pointed to other suspects.

• Weak defense: Mattan’s defense mounted little challenge to the prosecution case, calling few witnesses and doing little to discredit the inconsistencies.

The jury took just over an hour to convict. He was sentenced to death.

The execution:

On September 3, 1952, Mahmood Hussein Mattan was hanged at Cardiff Prison, still proclaiming his innocence. His wife and children were left to endure the stigma of being associated with a convicted murderer.

Cultural Context

Postwar Britain saw intense racial prejudice, particularly in working-class port cities. Somali, Yemeni, and Caribbean communities faced discrimination in housing, employment, and justice. Mattan’s case reflected how race and “foreignness” could become evidence in themselves.

For decades, Mattan’s widow and sons campaigned to clear his name. Their efforts culminated in 1998, when the Court of Appeal reviewed the case. Judges ruled that Mattan’s conviction had been a “serious miscarriage of justice”:

• The police had suppressed evidence that undermined key witnesses.

• The trial had been conducted in an environment of overt racial prejudice.

• The conviction was declared unsafe, and Mattan was posthumously acquitted.

Aftermath:

The British government later issued a formal apology to his family. They were awarded compensation — though, as his son poignantly remarked, “Money can’t bring my father back.” The case became the first wrongful conviction to be overturned under the 1998 Criminal Cases Review Commission, a body established to address miscarriages of justice.

Legal Legacy

Mattan’s case is now taught as a landmark example of how prejudice, weak defense, and prosecutorial misconduct can conspire to kill an innocent man. It underscores the importance of:

• Full disclosure of evidence by the prosecution.

• Challenging racial bias in the justice system.

• Independent bodies like the CCRC to correct miscarriages of justice.

Why this belongs in “Wrong Person Executed”:

Mahmood Hussein Mattan was executed after a trial steeped in racism and flawed testimony. His eventual acquittal — nearly half a century later — confirmed that the state had taken the life of an innocent man. His story is both a tragedy of his time and a warning for ours: justice systems are only as strong as their fairness to the most marginalized.

________________________________________

5. Colin Campbell Ross (Australia, 1922)

The case in brief:

On December 30, 1921, the body of 12-year-old Alma Tirtschke was discovered in Gun Alley, a laneway off Little Collins Street in Melbourne. She had been strangled and sexually assaulted. The crime shocked the city: a child murdered in broad daylight in the heart of Melbourne’s business district. Within days, police focused their attention on Colin Campbell Ross, a 29-year-old wine bar owner whose premises were near where Alma was last seen.

The investigation:

Ross was a struggling small businessman with a prior conviction for attempted rape — a fact that immediately put him under suspicion. Witnesses claimed to have seen Alma outside his wine saloon, though accounts conflicted. Police found a blanket in Ross’s home with what they believed to be hair resembling the victim’s. This hair became the key forensic evidence against him.

• Witness testimony: A series of dubious witnesses testified, including a woman who later admitted she had been offered a £1,000 reward for information. Their statements often contradicted each other.

• The hair sample: Microscopic comparison of hairs from Ross’s blanket with those from Alma’s body was presented as conclusive proof. At the time, forensic hair analysis was in its infancy and poorly understood.

Despite the lack of direct evidence — no blood, no eyewitness to the crime itself — Ross was charged with murder.

The trial:

• Date: February 1922 at the Melbourne Supreme Court.

• Prosecution: Emphasized Ross’s prior record, the “matching” hair, and witness claims that Alma had been seen near his saloon.

• Defense: Ross denied knowing Alma, denied she had ever entered his bar, and insisted the hair evidence was unreliable. He presented character witnesses, but his criminal history weighed heavily.

• Verdict: After a sensational trial, Ross was found guilty of the rape and murder of Alma Tirtschke.

On April 24, 1922, Ross was executed by hanging at Melbourne Gaol, still proclaiming his innocence. His final words reportedly included: “I am innocent. I never saw the child.”

Cultural Context

Australia in the 1920s was still deeply influenced by British legal traditions, with great weight given to circumstantial evidence and character judgments. Forensic science was seen as modern and authoritative, even when the techniques were untested. Ross’s prior record and working-class background made him an easy scapegoat in a case that horrified the public.

The long fight for justice:

For decades, doubts about Ross’s conviction lingered. Legal scholars, journalists, and civil libertarians pointed to unreliable witnesses, the lack of motive, and the dubious hair evidence. Ross’s family, especially his sister, campaigned tirelessly to clear his name.

In the early 2000s, advances in forensic technology allowed for DNA re-testing of the original hair samples, which had been preserved in state archives. In 2008, modern analysis proved conclusively that the hairs used to convict Ross did not belong to Alma Tirtschke. The cornerstone of the prosecution’s case had been false.

The pardon:

Following the new forensic results, the Victorian government issued a posthumous pardon to Colin Campbell Ross in May 2008 — 86 years after his execution. It was the first time in Australian history that a pardon was granted on the basis of new scientific evidence.

Legal Legacy

The Ross case has become one of Australia’s most notorious miscarriages of justice. It highlights:

• The dangers of overreliance on unproven forensic techniques.

• The enduring risk of wrongful execution when courts bow to public pressure for a swift conviction.

• The importance of preserving forensic evidence for future testing.

Why this belongs in “Wrong Person Executed”:

Colin Campbell Ross was executed for a crime he almost certainly did not commit, condemned by faulty forensics and questionable testimony. His posthumous exoneration nearly a century later underscores the brutal finality of the death penalty — and how easily fear and flawed science can lead to the death of an innocent person.